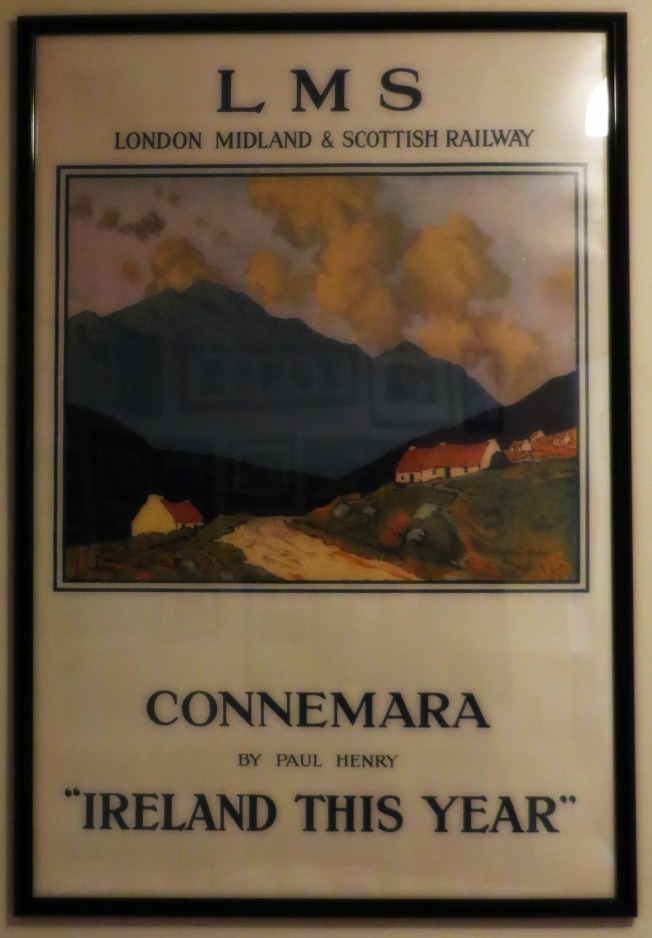

A better person would have taken a non-reflective photo for you.

There’s an old travel poster hanging above our bed back in Seattle that says Connemara “Ireland This Year”, and since we got married, it has been a daily reminder that this wild and wide-open hunk of Ireland has been on our to-do list. Kerry’s landscape might be green and lovely, and the lush mountains and charming villages dotting the countryside of Wicklow might make it a big tourist destination, but Connemara haunts my dreams.

It is moody in places and feels desolate in others, I often don’t know if I’m looking at rocks or sheep, but it stirs my soul and calls to me every couple of years. Once I’m out there, I don’t even necessarily know what to do with myself, but I’m happy to be looking at bog cotton and the barren mountains and little thatched cottages that look like something from a dream of Ireland instead of the real thing. As Z guides the Galway Hooker along the narrow road, he says, “It’s a lot browner than I imagined,” and I’m so in love with where I am, that I don’t feel like I have to apologize that there are fewer of Johnny Cash’s forty shades of green here than in other parts of the country.

Connemara and a few of Johnny’s 40 shades.

A decade ago, I spent a week at a castle with a group of writers with ties to Aspen Words. We were at Kinnitty Castle in the Midlands and though it was lovely there and I had one of the most enriching writing experiences of my life—studying under novelist/memoirst Hugo Hamilton and spending a day and evening with novelist Colum McCann—I felt let down not to be in Connemara. When I arrived at the castle, which had been in existence in one form or another since the 13th century, I felt off my game. It was not in the Ireland that I was most familiar with, and the others in the group were all older than me and richer than me. We had in our midst, amongst others, a couple on the Fortune 400 list and a countess. The first night, alone in my four-post bed, staring out the Gothic window, I was near tears and ready to head home because I felt so out of place. But then my cousin Mary called me to see when I’d be coming “home” to County Galway, and suddenly, I felt not so alone and more than a little spoiled that I would let myself get into this low state when I was staying in a castle in very princess-y accommodations. Never mind I didn’t have a second home (or even a first one) and hadn’t been a major donor to a presidential campaign.

That week at Kinnitty was grand. Hugo Hamilton’s writing workshops changed the way I led my own, I realized that despite the size of their stock portfolios the people in this group really were just people, and I made a few friends. The owner of the castle chatted with us one night in the dungeon pub about the various ghosts in residence, and he seemed a little too pleased that a ghost hunting show had come to the castle to film paranormal activity. Later though, talking to two different members of the wait staff, the tales of haunting seemed more legitimate. One server said she refused to go in the banquet hall alone and reported that someone down in the Dungeon Pub had seen a hooded monk there. It felt like the perfect setting for a murder mystery like Ten Little Indians, where one by one, various guests are picked off.

Kinnitty Castle, 2005

With Kinnitty as my only Irish castle experience, I’m not sure what to prepare myself for when Z and I pull off the N59 in Clifden looking for Abbeyglen Castle Hotel where we’ll be spending the night. As we wind our way up the drive and spill into an overflow parking lot, the buildling is impressive enough there on the hillside overlooking the little town and the estuary that eventually spills into the Atlantic. It’s more Victorian than I’d imagined, and with its helipad and tennis courts it seems more like a stately home. It’s too early to check-in, but when we enter the lobby it’s clear that it is more 19th century than actual archers-in-the-turrets castle like we were clambering around in Wales. Though it is much bigger, it gives me a sense of Fawlty Towers at first glance, perhaps because there is a parrot near the reception desk that says, “Goodbye” whenever guests walk past.

Abbeyglen Castle Hotel, complete with throne to greet you and a piece of our luggage.

Mary has recommended the castle restaurant for our evening meal where, it seems, you eat what is being served for the night instead of ordering from a menu. I am a picky eater with the palate of a four-year-old and the delicate stomach of an octogenarian, so after we walk back into town to kill time, we phone the front desk multiple times to see what will be on the evening’s menu so we’ll know if we need to make alternate plans. Every time we call, we’re told to call back later because the chef hasn’t decided yet what he’s serving. On the last call, the receptionist says brightly, “Whatever it is, I’m sure it will be lovely. It always is!” We decide that a better plan for us might be to have an in-room picnic, so we walk to the nearest Clifden Gas-n-Sip and piece together the makings of a meal, and then head back to check in. Later, when we finally get the final word on the menu, it was the correct choice (for me anyhow–I am not a duck confit kind of person).

Abbeyglen Castle grounds looking towards Clifden

Our room is massive with a canopy bed, a fireplace, wing-back chairs, and a bathroom that our living room in Seattle would easily fit into, complete with a claw-foot tub where I spend an hour soaking and pretending my lady-in-waiting will be ushering me into a velvet robe when I get out.

The bed I’ve been looking for my entire life.

We watch rugby in our room, sitting in the worn wingback chairs by the fireplace, our feet propped on the single bed that randomly juts into the sitting area, and nosh on our meal. Z says, “This place is an interesting combination of ‘posh’ and ‘worn’, isn’t it?” It is. But I feel strangely pleased by this combination and by our dining choices. It is comfortable, and I don’t feel haunted or homesick at all. Also, there is supposedly a tie in our family lineage to Eleanor of Aquitane, so that canopy bed is feeling like my divine right even if we are in Ireland instead of England or France.

Abbeyglen Castle room with bonus single bed.

What does make me homesick, however, is the lack of room wi-fi. After dinner, we head to the lobby to check our mail. Though I know it is “ugly American” behavior, I feel indignant that I should be staying in castle where the website boasts fine amenities, but then I have to sit in the lobby with all the other guests glued to their screens. I grumble. It feels like an airport, as if we’re killing time on Facebook before our planes take off to their disparate destinations. That said, I am wearing my glorious green cape, which makes it feel slightly more glamorous than the all Internet Call Shops I used to have to frequent on my Irish trips.

My kingdom for a hotspot.

We leave early the next morning for the teeny town of Cleggan and the ferry that will take us to Inisbofin, an island hanging off the western coast and a favorite spot of mine since I went there ages ago with another group of writers and poets Mickey Gorman and Gerry Donovan. Because we’re so early and the ferry doesn’t leave for a couple of hours, we wander into a pub next to the field where we’ve been directed to park, ask if they mind if we sit with our luggage, which still seems too huge despite John and Mary having reduced our load by half. We sip early-morning-appropriate beverages, eat crisps—the only food on offer at this time, write postcards, and wander outdoors to introduce ourselves to the neighbor donkey. While I sit there, I think about my fantasy of living in a small village and how idyllic it would be, but then simultaneously realize how much I’d feel like I was in a goldfish bowl with everybody down the pub knowing your business. There’s no pleasing me.

Cleggan welcoming committee.

Finally, we roll our bags down to the dock to catch the ferry. A decade ago when my mother and I made this same trip, we stood at the back of the small boat like a pair of lunatics, getting soaked from the waves that splashed us, and cackling with glee as the boat heaved and ho’d through the icy Atlantic. I’ve been telling Z that the ride will be rough, but when we arrive at the dock, the boat is much larger than last time and it turns out we’ve had rougher rides on the sedate Washington State Ferry System than we will on this one.

ShellE, regular stowaway on all my journeys, enjoys the Inishbofin ferry.

We opt to sit out front and look at the mountains, the craggy cliff faces, and eventually as we nose our way into the island’s harbor, Cromwell’s barracks from the 16th century, where supposedly Grace O’Malley, the pirate queen, once lived. (Grace O’Malley seems to have lived a great many places in the west of Ireland!)

I prefer thinking of this as Grace O’Malley’s castle instead of Cromwell’s barracks, but suspect there is more historical accuracy in the latter.

On my other two trips here, I’ve stayed at the Doonmore Hotel, high up on the hill, partly because it was the only hotel on the island. On one of the rainy, gloomy days Mom and I were there, the power was cut while repairs were made to the cable that brings the electricity to the island, a relatively recent development: the island wasn’t electrified until the 1980s. So Mom and I poked our noses into the hotel lounge to see if it was a place where we could pass some time, and as luck would have it, the owner, Mrs. Murray, was there. She ushered us in, commanded someone to bring a pot of tea and biscuits, and we settled in for the rest of the afternoon, getting to know her and learning about the island hotel life. It was one of those delightfully happy accidents that happens to me only in Ireland. Because of this fond memory, I can’t say what made me book our room at the newer, closer-to-the-docks, Inishbofin House Hotel, but I did. Nearly as soon as we arrive there, who do I spy but my cousin Brendan (Catherine’s brother), who has been working at the hotel for the summer. Another happy accident I wouldn’t have had the benefit of if I’d been true to the Doonmore.

Inishbofin, heather and sheep/rocks.

Our room has a view of the harbor, and it’s glorious out. Possibly the most beautiful day I’ve ever seen on all of my visits, and therefore I cannot explain what compels me to leave my camera back at the hotel when we venture out. I have no photographic evidence of how sunlight hits every surface in a perfect, magical way, and scenery looks like it was fabricated by a Hollywood prop department. But it’s true. Everything sparkles and shines.

Inishbofin, view from our room.

I grew up with access to the country—spent summers frolicking in the cow pasture at my grandparents’ farm, played with kittens in the hay mow at my aunt’s farm—but until I am on Inishbofin, it is a quality of freedom that I forget ever having had. (Possibly, because there are no parental units here warning us off of a particular walk or activity, it is actually more free than those childhood rambles.) If you asked me what there is to do on the island, I would be honest and tell you the truth as I see it: absolutely nothing. And it is glorious.

Inishbofin

There are cars on the island, but they aren’t really a worry and the drivers seem to know that tourists will be gawping in the middle of the road. (Plus, Irish drivers are at least 80% more careful and polite than in the US, even on the mainland.)

The narrow roads of Inishbofin.

So we walk. We talk to cows. We watch sheep scuttling across a distant hillside as a dog nips at their heals. We stop at an old cemetery and marvel at the Celtic cross gravestones marking the resting places of centuries of island dead. When we get to the water I’m shocked by how the best descriptor for its color is sapphire. It’s windy and too cold to comfortably wade, so we find shelter next to a tall rock, eat a packet of crisps, and try to soak up all the beauty. We’re on island time and the ocean air relaxes us better than any drug could. We eat supper in the hotel restaurant and sleep well.

On the island, we sleep like babies, but fortunately not like this one, found lashed to a post on one of our rambles.

The next day I’m determined to see the seal colony on the other side of the island. On the last two trips here it has been a failed goal due to weather or lethargy, so Z and I pack our lunch, grab the map that has little on it other than three trails we can take. I pick the one with “seal colony” written along the far coast and we start walking. On the way, we pass the public school, where the children have painted murals depicting the history of Inishbofin, including the 1927 Cleggan fishing disaster that is mentioned in all of the island literature because it was so devastating, the island getting electricity, and a mysterious panel from the 1960s called “The Cocoa Years” that leaves me hankering for a café and an explanation, neither of which is forthcoming.

The Cocoa Years predated the Electricity Years. Which would you pick?

The ground on our walk is uneven, rocky most places and then surprisingly spongy when we reach the bog—from which turf is cut to heat island homes. There in dark peat someone has spelled out with small rocks, “Aisling, will you marry me?” and someone, one hopes not Aisling, has spelled out beneath it a rocky “NO.”

Maybe next time DON’T propose in the bog?

We reach the seal colony, and there they are, waiting on us, bobbing up in greeting. I peer west and pretend to see America. We settle down on a rock, ready to tuck into our picnic when the midges start biting. We move. They follow. We move again. There’s no getting away from them unless we keep moving, so we have a walking picnic instead, munching and traipsing across the hillside. It’s not part of my magical dream and we’ve walked about six miles so I had been looking forward to sitting down for a while, but I can, on occasion, still tap into my inner Girl Scout and adapt to changes of plan.

Amerikay is out there somewhere.

The place is covered in sheep and thus, sheep crap, but it is my idea of heaven. We run into very few people, so the walk is desolate (other than the sheep). I spin in circles with my arms outstretched, Julie Andrews style, and sing the first few bars of “The Hills are Alive” and Z just shakes his head.

Steep hill, sheep crap, midges–yet I couldn’t be happier here.

I love being out here with no place to be, no one pushing us along to the next tourist site, no sense that I should be dong something better with my time. In the front of my journal, I have written “You are here; this is now.” It’s meant to remind me not to live in the future or the past, but I daily fail to live up to this goal and distract myself from the present with some memory or plan. Even if we are at a beach somewhere lovely, I often find that I’m troubled because I feel if I close my eyes for a nap or pick up a book to read, that I am somehow not fully taking in the moment. But on this day, hiking around these sheepy hills? This day, I reach my goal.

Inishbofin.

As we walk along the edge of the island, we can see the derelict buildings on Inishark in the distance, an island that is no longer inhabited. We hear the water crash against the rocks below us. A colony of big rabbits has threatened to take over the island, and I’m happy to see so many of them only because I’m not an islander and don’t have to deal with the havoc they are wreaking.

A Bofin Bunny.

As we make our way back towards civilization, we pass the Doonmore and I say hello to it and think good thoughts about Mrs. Murray. By the time we make our way back to the hotel, we’ve hiked twelve miles and we’re both in need of Advil, but this day will be one of my favorite memories of this entire trip. In the evening, a traditional céilidh band is playing, and I nudge Z away from the room and towards the music for what to me is the cherry on the top of a perfect day.

Inishbofin cottage

Before we arrived, I assumed I could comfortably make this my last trip to Inishbofin in lieu of future trips to other islands I’ve never investigated, but after today, I’m not sure I’ll ever be done with this outpost. And what I don’t know yet but learn the next day when we leave the island is that Mrs. Murray has just died and as we are sailing back to the mainland tomorrow, her body will be returning to the island one last time. This is no “happy” accident, but even so, I feel weirdly lucky to have been on Inishbofin, thinking of that afternoon tea with her eleven years ago, when her own island story was ending. It’s a melancholy thing, but it warms me.